2026 Executive Order 9066 (Description) - February 19, 1942 is a Significant Date for the Japanese American CommunityNEW

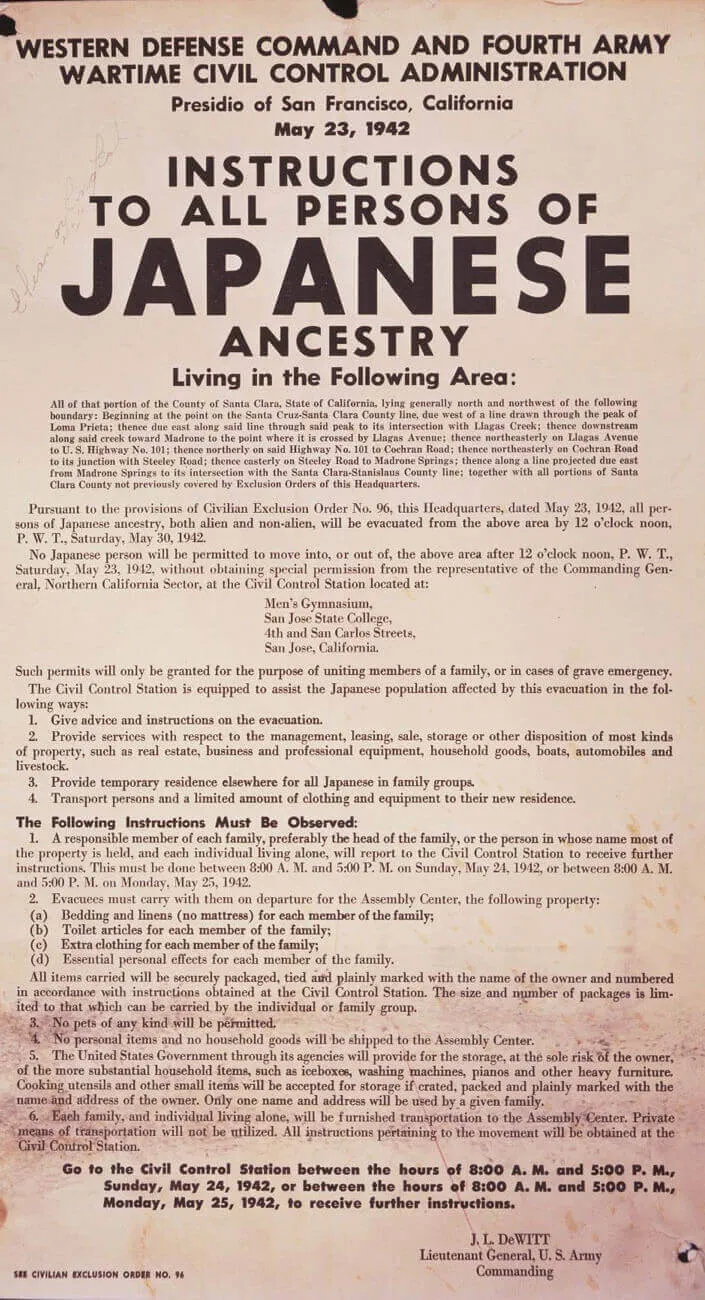

The Order. The order authorized the Secretary of War and U.S. armed forces commanders to declare areas of the United States as military areas "from which any or all persons may be excluded," although it did not name any nationality or ethnic group. It was eventually applied to one-third of the land area of the U.S. (mostly in the West) and was used against those with "Foreign Enemy Ancestry" - Japanese.

The order led to the internment of Japanese Americans or AJAs (Americans of Japanese Ancestry); some 120,000 ethnic Japanese people were held in internment camps for the duration of the war. Of the Japanese interned, 62% were Nisei (American-born, second-generation Japanese American and therefore American citizens) or Sansei (third-generation Japanese American, also American citizens) and the rest were Issei (Japanese immigrants and resident aliens, first-generation Japanese American).

Japanese Americans were by far the most widely affected group, as all persons with Japanese ancestry were removed from the West Coast and southern Arizona. As then California Attorney General Earl Warren put it, "When we are dealing with the Caucasian race we have methods that will test the loyalty of them. But when we deal with the Japanese, we are on an entirely different field."[1] In Hawaii, where there were 140,000 Americans of Japanese Ancestry (constituting 37% of the population), only selected individuals of heightened perceived risk were interned.

Americans of Italian and German ancestry were also targeted by these restrictions, including internment. 11,000 people of German ancestry were interned, as were 3,000 people of Italian ancestry, along with some Jewish refugees. The Jewish refugees who were interned came from Germany, and the U.S. government didn't differentiate between ethnic Jews and ethnic Germans (jewish was defined as religious practice). Some of the internees of European descent were interned only briefly, and others were held for several years beyond the end of the war. Like the Japanese internees, these smaller groups had American-born citizens in their numbers, especially among the children. A few members of ethnicities of other Axis countries were interned, but exact numbers are unknown.

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was responsible for assisting relocated people with transport, food, shelter, and other accommodations.

Find "Remembrance Events" in the Community

Japanese Americans & U.S. Constitution - Click for Media Experience - or Print Version

http://americanhistory.si.edu/perfectunion/experience/index.html

United States Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on February 19, 1942 authorizing the Secretary of War to prescribe certain areas as military zones. Eventually, EO 9066 cleared the way for the relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps.

Pre World War 2

Between 1861 and 1940, approximately 275,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawaii and the mainland of the United States the majority arriving between 1898 and 1924. Japanese controlled less than 4 percent of California's farmland in 1940, but they produced more than 10 percent of the total value of the state's farm resources. Envy over economic success combined with distrust over cultural separateness and long standing anti-Asian racism turned into a disaster when the Empire of Japan Attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Lobbyist in the United States gain American support and pressured Congress and the President to remove persons of Japanese descent from the west coast.

Opposition

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover opposed the internment, not on constitutional grounds, but because he believed that the most likely spies had already been arrested by the FBI shortly after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.[2] First lady Eleanor Roosevelt was also opposed to Executive Order 9066. She spoke privately many times with her husband, but was unsuccessful in convincing him not to sign it.

Post-World War II

Executive Order 9066 was rescinded by Gerald Ford on February 19, 1976.[4] In 1980, Jimmy Carter signed legislation to create the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). The CWRIC was appointed to conduct an official governmental study of Executive Order 9066, related wartime orders, and their impact on Japanese Americans in the West and Alaska Natives in the Pribilof Islands.

In December 1982, the CWRIC issued its findings in Personal Justice Denied, concluding that the incarceration of Japanese Americans had not been justified by military necessity. The report determined that the decision to incarcerate was based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." The Commission recommended legislative remedies consisting of an official Government apology and redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors; a public education fund was set up to help ensure that this would not happen again (Public Law 100-383).

On August 10, 1988, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, based on the CWRIC recommendations, was signed into law by Ronald Reagan. On November 21, 1989, George H.W. Bush signed an appropriation bill authorizing payments to be paid out between 1990 and 1998. In 1990, surviving internees began to receive individual redress payments and a letter of apology.

Reference: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executive_Order_9066

Disclaimer: Please double check all information provided on our platform with the official website for complete accuracy and up-to-date details.

Thursday, 19 February, 2026

Event Contact

Executive Order 9066Event Organizer Website

Visit Organizer Website

Get More Details From the Event Organizer

Event Location Website

Visit Location Website

For More Location Details

Event Information Can Change

Always verify event information for possible changes or mistakes.Contact Us for Issues